A common problem with photos is lack of sharpness. The image is either soft, or out of focus, or the wrong part of the image is in focus, or … the list of possible issues is a long one.

Just like exposure, focus is one of the parameters that the photographer must learn to control in order to create images that show what he or she visualized before pressing the shutter release.

This is the first of a series of posts that I will call “Image Clarity 101”. The name is a tip of the hat to John B. Williams who wrote the excellent “Image Clarity: High-Resolution Photography, which – alas – seems to be out of print.

I am going to look at what causes an image to be “sharp”. In later postings, I will explain what equipment and techniques to use to actually get an image to be “sharp”.

Focus

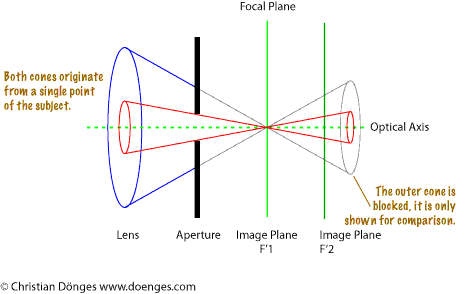

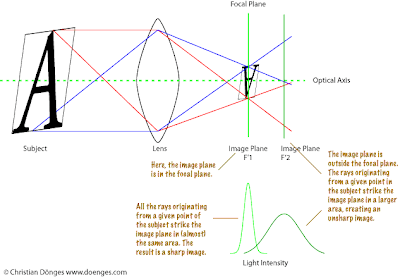

If we imagine that a subject is made up of an infinite number of minuscule points, each of these points emits an infinite number of light rays that hit the entire area of the camera lens. As the light rays pass through the lens, they are focussed on some point (the focal point) behind the lens, creating a cone of light.

Parallel to the lens plane is the focal plane, which holds an infinite number of focal points for all the visible points of the subject.

All of this is shown in the illustration below.

|

| Illustration 1: Focus Explained (simplified) |

The image plane is the surface the image is projected onto. This is where the film or image sensor is located. For an image to be in focus, the image plane must be the focal plane.

When you twist the focus ring on a lens, you are effectively moving the focal plane. When the image is sharp, the focal plane is located on the image plane.

Are you with me so far? Good!

Circle of Confusion

Now it gets a bit messier: since we are dealing with the real world, the light rays do not actually all converge on a single point, but form a small area, the circle of confusion.

In the illustration above, you can see that in the focal plane most of the light originating from a single point of the subject hits the small circle. As the image plane moves away from the focal plane, the light is spread over a larger area.

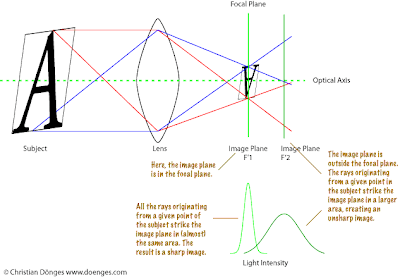

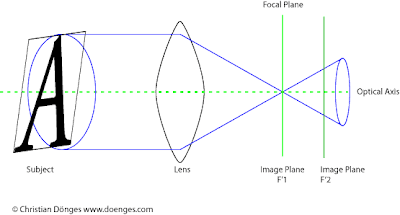

If this is too circle of confusion business to too confusing, have a look at the following, simplified illustration:

|

| Illustration 2: Cone of Light |

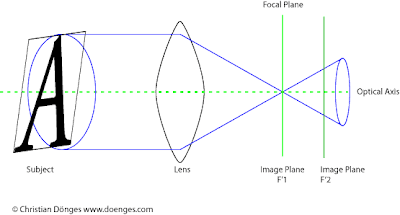

The subject is projected by the lens as a cone of light rays which strike the image plane. The tighter the cone is at the image plane, the close the image plane is to the focal plane.

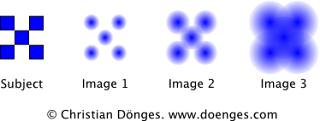

If the circle of confusion is small enough, the human eye will register it as a single point. How small the circle needs to be is perhaps a topic for another post. For the time being, we can assume that if the circle of confusion is somewhat smaller than a single photo site on the sensor, it will not be a limiting factor for the overall sharpness of the image.

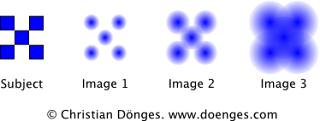

|

| Illustration 3: As the circle of confusion increases, the image becomes less sharp. |

So we reach a simple conclusion:

If a single point of the subject is rendered as a small enough circle of confusion, it will appear sharp in the image.

There is one important point to consider: all of what has been discussed above is only true for flat subjects and ideal lenses. In the next installment, we will look at sharpness for a non-flat subject.

If you don’t feel like getting an old book, you might try perusing the good old Wikipedia which contains much more on the subject.