If you want to use a PocketWizard FlexTT5/MiniTT1 on a non-Canon (make that non-Nikon if you have the recently released Nikon version) camera, you can do so by using Basic Trigger Mode which has been available starting with FW 4.100.

It’s quite simple to set up, if you know the magic sauce.

We will set Basic Trigger Mode in configuration C2. That way configuration C1 will remain available for use in ETTL mode. To keep things simple, we’ll use a MiniTT1 as transmitter and a FlexTT5 as receiver. You can actually use many FlexTT5 to drive multiple flash units. In this case, repeat the procedure for the FlexTT5 described below for every unit.

MiniTT1 (Transmitter)

1. Start the “Pocket Wizard Utility” on your computer. The screenshots below are from version 1.35. Other versions may differ a little. You can download the utility here for Mac and Windows.

2. Hook up the MiniTT1 to your computer using the supplied USB cable. The MiniTT1 should be turned OFF.

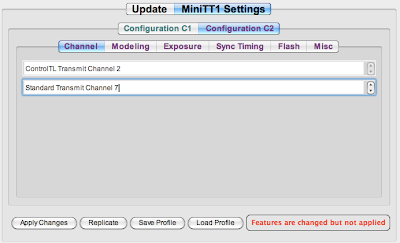

3. Go to Configuration C2 >> Channel and set the Standard Transmit Channel. The default is 2, you may want to change it to a different value if you expect to be shooting around other people with PocketWizards.

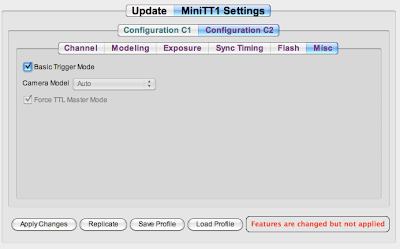

4. Go to Configuration C2 >> Misc and check the box Basic Trigger Mode.

4. Now press the button Apply Changes, confirm the question in the dialog box, and wait until the changes have been written to the device.

You are now done with the transmitter.

FlexTT5 (Receiver)

5. Now hook up the FlexTT5 receiver unit using the same USB cable. You can leave the PocketWizard Utility running, just remember to turn of the FlexTT5.

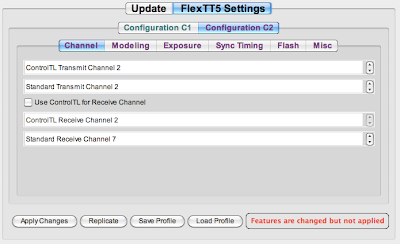

6. Go to Configuration C2 >> Channel and uncheck Use ControlTL for Receive Channel. Then set the Standard Receive Channel to the same channel you used as the Standard Transmit Channel in step 3. In this example, I used 7.

7. Press the button Apply Changes, confirm the question in the dialog box, and wait until the changes have been written to the device.

You are done with the receiver.

Repeat the receiver procedure with any other receivers you want to trigger simultaneously.

Let’s test it to see if it works:

Hook up a flash to the FlexTT5, turn on the flash, and set it to M (manual mode). Then turn on the FlexTT5 to setting C2.

Next, attach the MiniTT1 to the hot shoe of your camera and turn it on to setting C2. Then turn on the camera.

If you press the camera shutter release button, the flash should fire. Congratulations, it works!

I tried this using an Olympus E-P1 with a Canon 580 EX II and it works just like a cable – without the wires. 😉