In the last post, we looked at how a sharp image is created optically. In this post, we will look at how the physics render non-flat objects.

If all the points of the subject are in the same plane, they will all render with the same size circle of confusion in the image plane. This is the case if the subject is perfectly flat.

For non-flat subjects, the points of the subject are located at different distances from the image plane. So the projected points will have a minimal circle of confusion in different image planes. Since there is only one image plane, the projected points will all have different size circles of confusion – which means they will all be of different sharpness.

Each circle of confusion that is small enough will appear to be sharp. The distance from the nearest to the furthest point which are just rendered sharply is the depth of field.

The depth of field is determined by the distance of the subject from the camera, the focal length of the lens, and the aperture.

Some simple rules of thumb are:

1. The further the subject from the lens, the greater the depth of field for a given focal length.

The greater the absolute distance between subject and lens, the smaller the relative difference in distances for different points of the subject. Because of this, the size of the circles of confusion are very similar in size.

If you look at the distance scale on a lens, you will notice that the distance between markings decreases the closer you get to infinity. And, speaking of infinity, there is a point from which on everything is in focus if you focus the lens to infinity.

2. The shorter the focal length, the greater the apparent depth of field at a given distance.

The hyperfocal distance, or the distance from the image plane past which every subject point is acceptably sharp if the lens is focused on infinity, decreases the shorter the focal length of the lens. This is because the magnification decreases, so the circle of confusion for a given subject point is also magnified less.

Remember though, that this is true only for a fixed distance!

3. The smaller the aperture, the greater the depth of field.

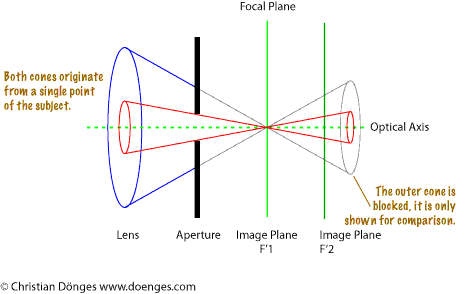

The smaller the aperture, the smaller the cone of light rays that passes to the image plane. Because the cone is smaller, the circle of confusion is also smaller.

In the illustration below, the aperture blocks the blue cone of light rays, only the red cone gets through. The circle of confusion on the image plane is smaller, so the image is sharper.

|

| Illustration 3: A smaller aperture reduces the circle of confusion |

Note that in practice, diffraction becomes a problem at small apertures. Diffraction will be discussed later in this series.

Bigger is not better

One important thing to keep in mind is that bigger is not necessarily better with depth of field. An image may actually be improved if (unimportant) parts are kept out of focus because the eye tends to focus (pun intended) on the part of the image which are sharp and tends to give the unsharp parts only cursory attention.

That said, if you are trying to render your image as clearly (sharp) as possible, you want to select your depth of field in such a way that the closest and furthest subject point which you want sharp are in focus.

For example, have a look at this image:

|

| Image 1: The forget-me-not in the foreground is sharp, the background blurred. |

The forget-me-not flower in the foreground is rendered in focus. The (rather cluttered) background is rendered out of focus. The eye of the beholder will pass over the out of focus parts, thereby de-emphasizing the non-essential parts and concentrate on the subject in the foreground.